"Never Sell"

"Never Sell"

Mike Swanton is that rare collector of pro football memorabilia who buys but never sells

|

"When I go to collectors’ shows or conventions, the dealers all know me, "Hey,’

they say, ‘here comes that football guy." Ernest (Mike) Swanton is telling me

this from behind a small desk in the office he's built just off the entrance

foyer of his 10-room ranch-style house in Brentwood, N.Y. A vacuum cleaner is

wheezing in the background and his teenagers have a radio playing.

If his home and what’s in it are any evidence, 46-year-old Mike Swanton is,

indeed, a "football guy." The walls of his office are plastered with montages

of football programs, ticket stubs, and newspaper accounts of games that date to

pro football’s scruffy, ragtag days. The den is adorned with pen-and-ink

sketches of NFL players that Mike has done, each neatly framed and autographed

by the star. Some of his more than 200 team posters -- "all different," he

tells me -- are on display too. Shelves strain under the weight of football

books by the hundreds.

Mike’s patio is decorated with hand-carved emblems representing the NFL, AFL,

and Canadian League. The bar in his card room is called "The End Zone."

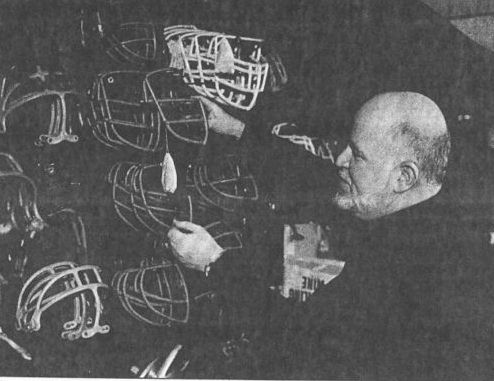

Helmets are everywhere. They’re stacked atop file cabinets and hang from the

ceilings. They’re displayed in Lucite cases and in long rows on bookcases.

They hang from pegboards and racks and are stored by the dozens in cardboard

cartons and big equipment bags that bear team logos.

More than a few dealers rank Mike as the country’s No. 1 collector when it comes

to pro football memorabilia. Pro magazine once called him a "nostalgia nut."

The Smithsonian Institution has happily accepted football items that Mike has

donated. So has the Pro Football Hall of Fame, for whom Mike occasionally does

"detective work," tracking down long lost antiquities, such as the Miami Seahawk

program books he’s now sleuthing for them.

Mike, who is executive director of the Guide Dog Foundation for the Blind, has

been deeply involved in the acquisition of pro football memorabilia since 1970.

"I used to be an architect," he says. "I was busy all the time, traveling all

around the country. I was also devoting lots of my spare time to a number of

voluntary service organizations. I was trying to do too much. Then I had a

series of anxiety attacks. I had to cut down. I had to learn to relax. I

needed a hobby. So I started sketching portraits of football players, first the

Giants and the Jets, because they were nearby.

"Then I did some of the Green Bay Packers -- Carroll Dale, Boyd Dowler and Bob

Schnelker, a Packer coach at the time. It ended up with me swapping my sketches

to them in exchange for a game ball autographed by all the players.

"After that, things exploded. In the next few years, I did more than 200

sketches and paintings of players. And I often swapped them for autographed

balls or other souvenirs."

Mike is skilled as an artist. A color portrait he did of Bert Jones was used as

the cover for the 1977 Football Register. The same year, the cover of the

Official Baseball Dope Book displayed a Thurman Munson portrait of his.

From autographed portraits and game balls, Mike started branching out,

collecting almost anything that had to do with pro football -- ticket stubs and

press passes, program books and press guides, face masks and helmets.

Did you ever hear of the Stapleton Stapes? Based in Staten Island, N.Y., the

Stapes were an NFL team from 1928 through 1932. Mike has most of their game

programs.

Helmets are his specialty. He has 450, mostly plastic, but about 150 old

leather helmets and one rare rubber model. In his cellar, there’s a shop

equipped with special tools and hardware required to refurbish helmets.

"I’ve got a helmet that dates to 1904," Mike says. "It’s older than any helmet

in the Hall of Fame." He shows it to me. It’s black and made of soft leather,

and it fits close to the skull, about the way a knit hat fits, except it has ear

flaps. In those early days, blows to the head were absorbed by the head.

Mike’s collection is an education in the evolution of the helmet, showing how

the addition of bands of leather at the top and across the forehead gradually

led to the development of the modern suspension helmet. Mike has several

samples of the first plastic helmets, which date to 1939.

Mike is also an expert on the logos that teams affix to their helmets. This

practice dates to 1948, the year a running back named Fred Gehrke hand-painted

Rams’ horns on each of the team’s helmets. I expected Mike to have one of the

actual helmets that Gehrke painted. He’s working on that. The best he could do

was to show me a replica.

"Players were painting their helmets long before Gehrke got into the act," Mike

says. "They painted them with solid colors, often white. The paint

waterproofed the leather. It also hardened the leather, making the helmet more

of a weapon."

Mike has acquired much of his memorabilia by prowling about flea markets. "You

never know what you’ll find at a flea market," he says. "That’s where I’ve

gotten most of my leather helmets. Garage sales are good, too. You can

sometimes pick up a helmet for only a dollar or two at a flea market or a garage

sale. Of course, you have to bargain. But bargaining is half the fun of it."

Mike also adds to his supply by visiting the firms that reconditions football

equipment. "Except for minor repairs, pro and college teams don’t maintain

their own equipment," Mike explains. "There are companies that do it for them,

maybe as many as a hundred of them around the country, firms like Raleigh

Reconditioning up in Westchester County, and Capital Varsity outside of

Cincinnati.

"When the season is over, teams send all of their equipment to one of these

companies. The helmets get new parts and new suspension systems. They’re

painted and new logos are applied. When I’m on a business trip out of town, I

visit these companies, and I ask them if I can go through their junk rooms,

their garbage. When I find something I want, we negotiate.

"I also visit boys’ clubs and high schools. In the old days, pro teams used to

donate their old and worn equipment to PAL teams, YMCAs, or parochial high

schools. Public schools often couldn’t accept used equipment, because of

regulations that said their equipment had to be purchased new," Mike explains.

"So I go to these clubs or schools, and ask if they have any old equipment. At

Iona Prep School in New Rochelle, N.Y., I once got three equipment bags filled

with old stuff." Mike and his family -- his wife, Joan and their three sons and

daughter -- once took a football vacation, setting out in their station wagon on

a journey that covered 6,325 miles in 13 days. That trip enabled them to visit

the offices of pro football teams in three Canadian and eight American cities.

They had breakfast with the Buffalo Bills and lunch with the Detroit Lions.

"When I visit team offices," says Mike, "I always try to get acquainted with the

football coach’s secretary. She’s a key figure. Send her a sketch or

something, and she can get it autographed by anyone, even the quarterback." On

such visits, Mike also loads up on programs, media guides and fan decals.

Mike also likes to acquire or dispose of memorabilia by swapping. Buying and

selling are something he tries to avoid. "Money would add a business aspect to

the hobby," Mike says. "And if I let my hobby become a business, I’d have to do

something else as a hobby."